Are we overproducing PhD students?

Every few years, reliably like clockwork, somebody claims that we’re producing too many PhD students. This week it is Nature’s turn:

The argument is always the same: There are many more PhD students than faculty jobs in academia, so we must be overproducing. This argument misses both what the majority of PhD students learn during their training and what their expectations are with respect to future jobs.

Let’s start with PhD students’ expectations. I talk to a lot of prospective and current PhD students, who are typically working in molecular or cellular biology, biochemistry, or data science/machine learning. About nine out of ten state that they’re not interested in an academic career. The vast majority plan to work in private industry post-PhD, and some hope for a position in government. This statistic likely reflects some disillusionment with academia in recent years, but in either case, assuming these students are honestly reporting their hopes and desires, they are expressly not entering PhD programs to become professors. Instead, they see the PhD as either an interesting opportunity for personal growth or an enabler for career paths that would otherwise have been inaccessible. As an example of the latter, one of my current PhD students worked in industry after completing her undergraduate degree, perceived a glass ceiling after a few years, and decided that pursuing a PhD would likely help her break through this barrier.

Now let’s talk about what PhD students learn during their training. I am most familiar with PhD programs in STEM, so I’ll focus on these types of programs. (I’ll show below that this is not a major limitation to my arguments.) STEM PhDs learn to independently manage complex and difficult projects, working over long periods of time through all sorts of challenges and setbacks. They learn to question their results, to come up with alternative approaches, to objectively assess and analyze data, to communicate their results in written and oral form, and to ultimately bring projects to completion. These are highly transferable skills that come in handy in many different contexts. Almost any high level position with real independence in any profession will benefit from these skills. To be clear, I’m not arguing that a PhD program is the only way to learn these skills. Certainly they can be learned on the job as well. I am arguing though that a PhD program is a great way to acquire them, because it has guardrails and failsafes that on-the-job training does not. (During a PhD, you’re given a lot of leeway to try things out and mess things up. It’s much less likely that your job in private industry will be this tolerant.)

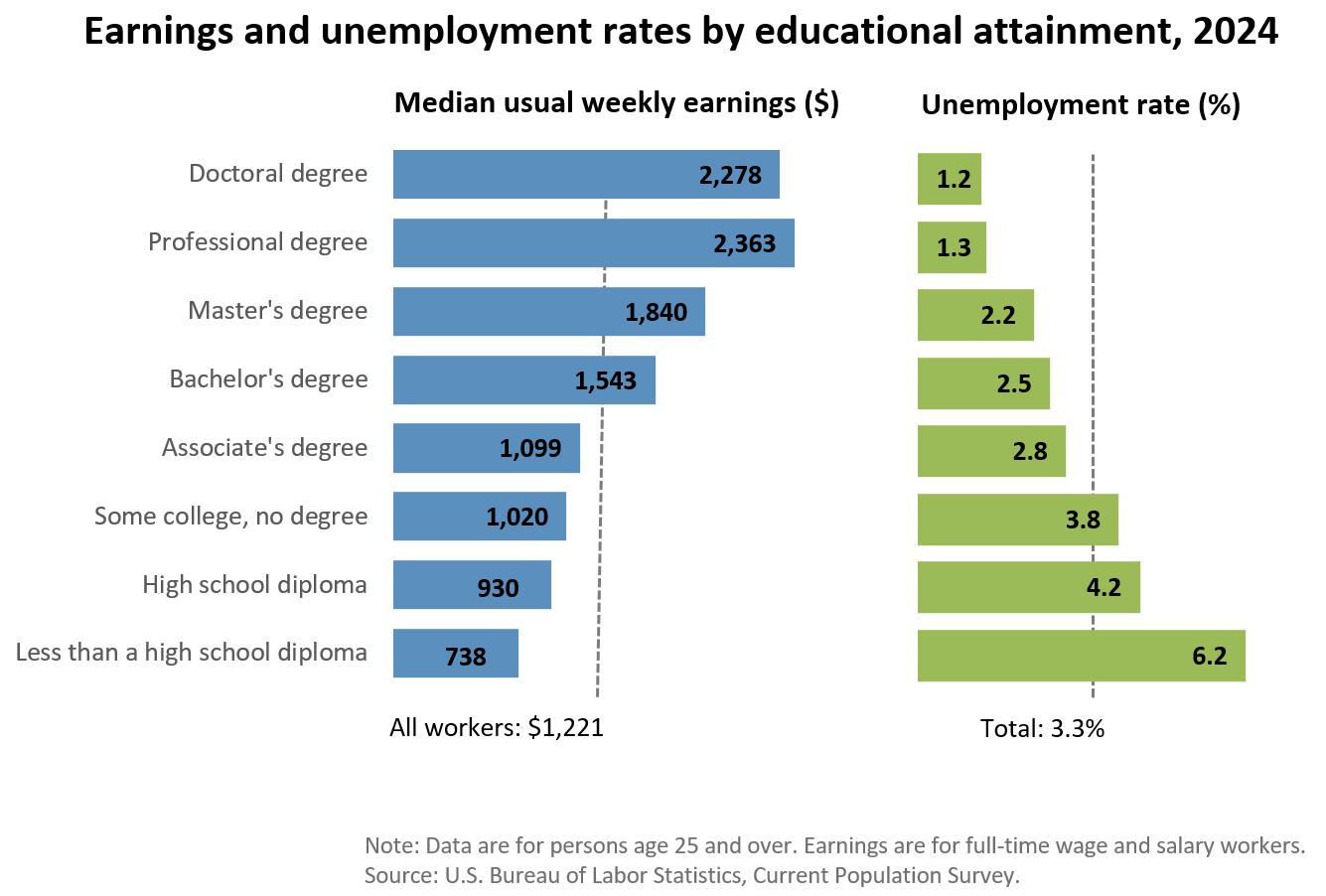

But maybe PhD students are deluding themselves about the perceived benefits of their advanced training, only to end up overqualified and underemployed? The data say that’s not the case. The US Bureau of Labor Statistics has consistently found that PhDs have the highest median earnings and lowest unemployment rates, approximately tied (and slightly behind on earnings) with professional degrees such as JDs and MDs.

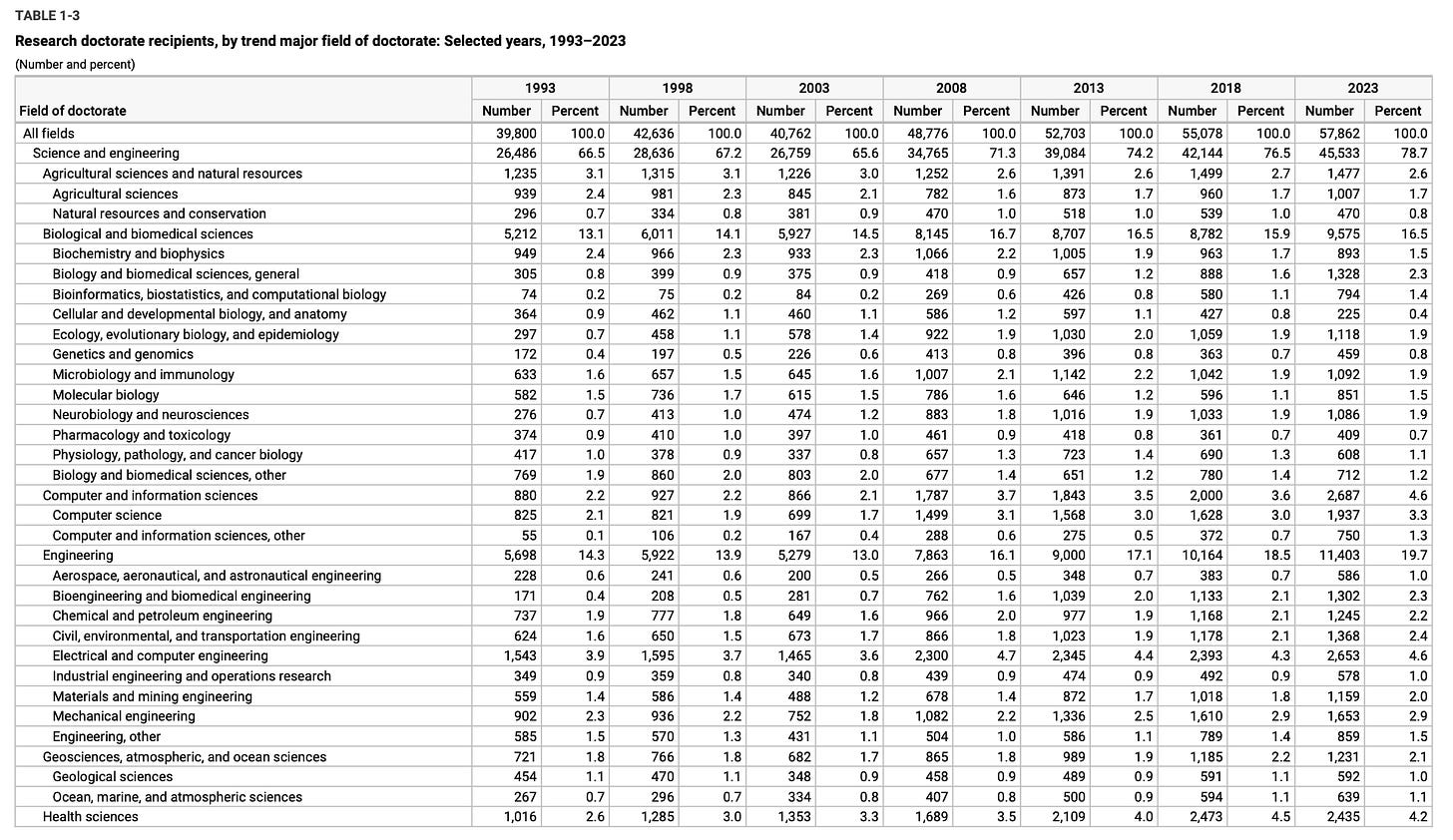

Another possibility is that even though PhDs in STEM fields receive broadly useful training, training in other areas (for example, history) is much more focused on an academic career path, and maybe we overproduce PhDs in those areas. According to the NSF, the percentage of PhDs in STEM has been increasing over the last 30 years, and it reached nearly 80% in 2023.

Maybe we are indeed overproducing history PhDs. I don’t know. But among all the PhDs we’re producing the history ones are only a small percentage (1.3% in 2023). This number seems too small to worry about. Most PhDs are not history PhDs.

It’s also worthwhile to ask where all the PhDs end up finding employment after they graduate. Another NSF publication sheds light on this topic. Almost forty percent work in higher ed, another forty percent in for-profit private industry, and the remainder in government, private non-profit, and self-employment. When reading these numbers, I was surprised seeing the percentage of PhDs working in higher ed to be so high. I would have expected a larger percentage to go to private industry. It’s important to remember though that not everybody working in higher ed is a professor. There are many non-faculty jobs in academia that require a PhD, such as staff scientist, instructor, and various types of administrator (example: director of a core facility). It would be difficult to fill these positions if we cut the number of PhDs substantially.

I will admit that my writing here is US-centric. The Nature article quotes statistics from South Africa, the UK, and China. It is possible some of these locales overproduce PhDs. I would still expect, though, that it depends both on the locale and the research area whether a PhD holder can expect a vibrant job market or not. A blanket statement of “there are too many PhDs” is almost certainly never accurate.

Finally, to be clear, I do think it’s possible to overproduce PhDs. Not everybody needs to get a PhD or has the ability to do so. But I don’t think we’re currently at this point. To me, signals of overproduction would be either a lack of qualified candidates, where we have more slots for PhD students than we can fill without lowering our standards, or a serious lack of job opportunities for our graduates. As of now, I don’t see either. And, as our world gets increasingly dependent on complex technology, I believe we will likely need more PhDs rather than fewer in the future.

I think your post brings up a few different ideas in my head.

1. Independent of the # of graduate students, I do think we should be pushing for more efforts of increased independence of graduate students. I do wonder if there are policy ways to do this (eg, funding stays with student over PI).

2. If a PhD is intended as a professional degree, it’s certainly not structured as one. Are there ways to make it shorter? One of the jarring things in tech & industry is how much responsibility is given to young talent so quickly. They tend to respond well to this, and I often see this learning is stunted when coming out of academia.

3. I also worry though; there is something really special about a PhD when it works. A seriousness about going into the wilderness, focused on a problem, and learning to find a way out. You usually don’t get the time/space to do that outside academia.

Anyways, no system is perfect, and the current plans to severely curtail academia is ridiculously short sighted. That said, it does bring up questions on how we can better structure/incentivize what we want as a society from these degrees.

"signals of overproduction would be either a lack of qualified candidates, where we have more slots for PhD students than we can fill without lowering our standards, or a serious lack of job opportunities for our graduates. As of now, I don’t see either."

At the end of 2021, I transitioned from my postdoc in bioinformatics to an industry position relatively seamlessly. However, having had to face the industry job market again over the last several months, I faced an brutal dichotomy of either "you are too qualified for this position" or "you don't have the experience necessary to do this job." Although some blame could be put on myself for not marketing myself correctly, especially in the beginning, I think something has changed fundamentally in industry, especially around the perception of what a PhD prepares for you for (exactly as you outline in your article about AI-level PhDs).