Nobody understands university finances

And certainly not the people talking about it on social media

Nobody understands university finances. Well, I’m sure provosts do, and university CFOs, and other university administrators deep in the depths of university accounting. But regular people do not, nor do students, and not even most faculty members. As a consequence, there are many misconceptions swirling around the airwaves. I routinely hear either complaints or well-meaning recommendations on how to fix some issue related to university finance (high tuition costs, lack of funding for research, etc.) that just don’t make any sense. So let’s do a very high level breakdown of the business lines universities are in and the funding streams supporting those business lines.

Universities engage in two separate (though intertwined) lines of business: education and research. For simplicity, here I will lump everything related to undergraduate degrees, Masters degrees, and other professional degrees such as MDs and JDs under education. I will lump any research activities and the training of researchers via PhD programs under research.

Now let’s talk about how these business lines are funded. Education is funded through tuition paid by students, through donations or endowments providing either scholarships to students or other funds covering university operations, and (for public universities) through various government subsidies. Research, on the other hand, is funded through government grants for specific projects, non-project-specific government funds allocated to research (in the US, these have historically come in the form of indirects, which provide a government subsidy in proportion to the overall university’s research program and success at competing for research funds), and donations or endowments, often also earmarked for specific projects or research areas. Importantly, tuition is not a source of funding for research activities, at least not directly. PhD students generally don’t pay tuition. Their tuition may be paid from research grants or other budgetary sources (such as the educational budget when they work as teaching assistants), but it is not an independent income stream for the university.

In the US, one unique aspect of the research side of a university’s operations is how decentralized and fragmented it is. A major research university may be spending $500 million a year on research, but that doesn’t imply it has a single, centrally managed research department with a $500 million budget. Instead, there are more likely a thousand separate independent units that spend $500k each. Each of these units has a person in charge (called the PI, for Principal Investigator, typically but not always a faculty member at the university) who is responsible for raising the funds, allocating the funds, and ensuring that the research progresses. The PIs essentially run little independent, self-sustaining businesses inside the university, and all the university does is provide infrastructure and administrative support. The consequence of this setup is that if a PI fails to raise the funds necessary to continue their research, that research unit disappears. A university will not generally rescue research operations that fail to attract funding, at least not for very long.

Now we can engage in some thought experiments as to what happens when various income streams get modified or disrupted. On the education side, if government subsidies or endowment incomes decrease, for whatever reason, tuition will have to increase to compensate for the shortfall. (It is notable though that the empirically observed relationship between government subsidies and tuition costs appears to be not as strong as one might expect.) Or, alternatively, to keep costs down, quality of service has to be reduced, which typically results in larger class sizes, fewer teaching assistants per student, more contingent faculty, etc.

On the research side, if government grants, government subsidies via indirects, or endowment incomes decrease, less research will be done, and fewer PhD students will be trained. There is no alternative source of funding that can compensate for the shortfall. Importantly, undergraduate tuition is not an appropriate funding stream for research, and you should not expect that universities would divert a substantial amount of tuition dollars towards research activities. Because of the fragmented nature of independent research operations inside a single university, the response to a changing funding landscape will be both rapid and uneven. As an example, if one day there were no more funding for astronomy, then astronomy research might collapse rapidly, while next door maybe AI research might continue unimpeded. In either case, though, we have to be clear eyed that universities are businesses operating under the constraints of supply and demand, and if demand for research activity decreases then they will adjust the supply accordingly. And demand for research is measured by the extent to which various funders are willing to pay for it.

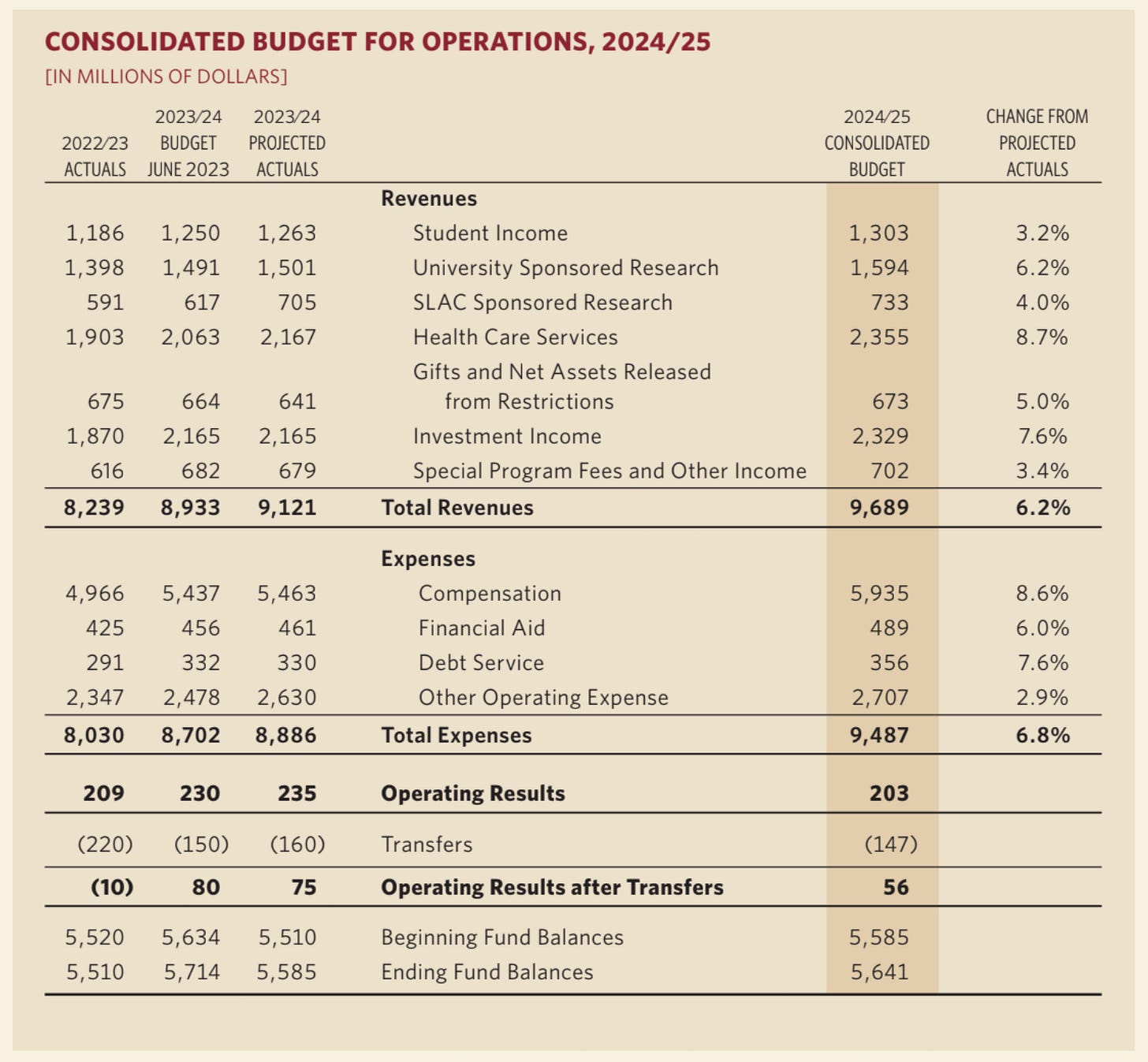

Let me close with some high-level numbers on the size of these budgets. In brief, they are massive. Major universities are multi-billion dollar operations. Consider Stanford, which has one of the largest endowments of any private university, of almost $40 billion. Well, they also have an annual budget of over $9 billion. And they spend around 5% of their endowment, in excess of $2 billion, on their annual expenses.

The Stanford budget is particularly large, but other universities have similar budgets. My employer, The University of Texas at Austin, has an annual budget of nearly $4 billion. For many universities, budget documents are public, and you can dive in and figure out exactly where moneys are coming from and where they are going. Finally, if you want an absolute deep dive into the depths of university finances, check out this book on the budget of a major biomedical research institution.

There are many more things that could be said about university budgets, and I may cover more specific topics in future posts. For now, I just want you to remember: education and research are two distinct activities, and they are funded from different sources.

Out of curiosity, have you seen any less traditional ways of funding a lab?

Would be super interesting to see the inflows and outflows of a major research department. The thing I’ve heard many times at ucla is almost all departments and divisions run in the red. Meaning research grants and overhead don’t pay for departmental expenses.

I would also say while teaching / research might be different inflows of money, I think they are also intertwined in the mindshare of what people focus their time and attention on.

All of this said, it’s also weird that universities are not more public with these finances. There is a lot hidden here and it breeds mistrust.