Have you ever seen a man with whiskers?

Or, you can't blame a 100-year trend on a technology that is barely 20 years old.

An article is making the rounds on Substack about how civilization is in decline and nobody can read or think anymore and it’s all due to screens and cell phones. The article is long, with numerous charts and figures, and I’m sure things are exactly as bad as it proclaims. After all, I myself recently said that “I learned mathematical concepts in high school that STEM PhD students in the US don’t necessarily know.” And yet, several aspects of the article bother me. Maybe it’s just my reflexive contrarian response to posts that declare the sky is falling. The world is typically more complex and nuanced, and this article in particular doesn’t excel at drawing out those nuances.

First, just because things are changing doesn’t mean everything is getting worse or changing for the reasons claimed. The article glosses over such complications, for example by focusing on averages: On average, math scores are down, reading scores are down, books contain shorter sentences.1 But the average can go down even as the variance increases and the top performers get better.2 It’s possible that we’re past peak literacy on a broad population basis—since many people now can obtain entertainment without having to read much—and yet civilization as whole may not be in decline and reading can continue to be critically important to a meaningful subset of the population. In fact, modern information technologies, including cell phones and the internet, provide nearly limitless access to information, and people take advantage of it in ways that would never have been possible even twenty years ago.

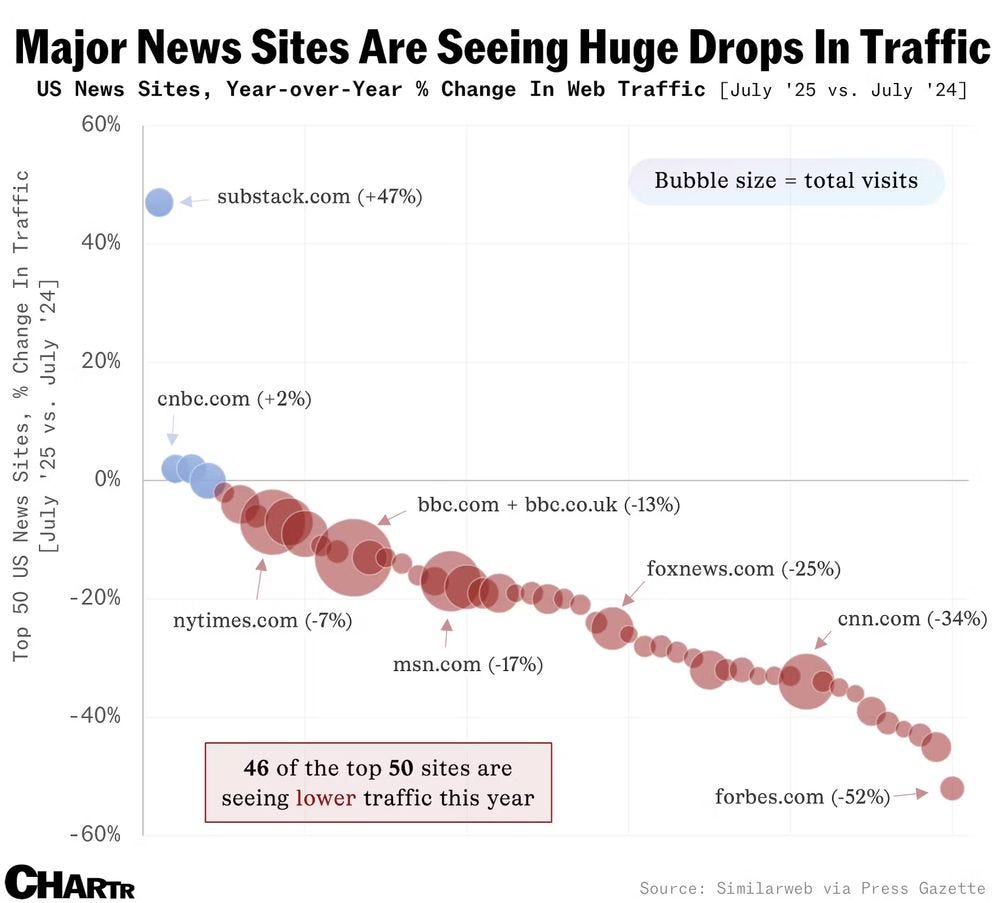

As a case in point, why are you reading this? Didn’t you get the memo? You should be on TikTok or Instagram or YouTube (but only in the shorts section, please). If reading is declining, how come a site like Substack, which is so centered around long-form and fairly intellectual content, keeps growing while much easier to consume content such as Fox News or CNN is declining?

In the same vein, who would have predicted the rise of the 3 hour podcast? It takes serious focus and effort to sit through one of those. Yet the genre is more popular than ever.

The article also relies heavily on associations, presented as if they necessarily reflected causal relationships. And it has issues with the time scales on which different trends can be seen. In particular, sentence complexity in books has been steadily declining for nearly a century, not something we can attribute solely to cell phones or even the internet.

I could go on about the various statistical flaws and logical fallacies in the article. (Don’t get me started on the regression of vote share versus TikTok interest in Romania, shown towards the end of the article.) But instead, for the remainder of my post here, I want to focus on one specific comment, regarding a study3 about the decline of reading comprehension in English literature students in the US. I quote:

A study of English literature students at American universities found that they were unable to understand the first paragraph of Charles Dickens’s novel Bleak House — a book that was once regularly read by children.

There are so many issues. First, these were students at two “regional Kansas Universities.” So please don’t imagine Harvard or Stanford undergraduates here. Second, the study was done in 2015. That doesn’t align well with the author’s thesis that cell phones and social media are to blame, does it? Third, I feel there’s a major confounding effect here. By using Bleak House, the study did not just assess students’ reading comprehension but also, implicitly, their knowledge and interest in 19th century English culture and way of life.4

In case you’re not familiar with Bleak House, this is the first paragraph of the novel:5

LONDON. Michaelmas term lately over, and the Lord Chancellor sitting in Lincoln’s Inn Hall. Implacable November weather. As much mud in the streets, as if the waters had but newly retired from the face of the earth, and it would not be wonderful to meet a Megalosaurus, forty feet long or so, waddling like an elephantine lizard up Holborn Hill. Smoke lowering down from chimney-pots, making a soft black drizzle with flakes of soot in it as big as full-grown snowflakes—gone into mourning, one might imagine, for the death of the sun. Dogs, undistinguishable in mire. Horses, scarcely better; splashed to their very blinkers. Foot passengers, jostling one another’s umbrellas, in a general infection of ill-temper, and losing their foot-hold at street-corners, where tens of thousands of other foot passengers have been slipping and sliding since the day broke (if this day ever broke), adding new deposits to the crust upon crust of mud, sticking at those points tenaciously to the pavement, and accumulating at compound interest.

I don’t know about you, but for me the first sentence, a mere 13 words, contains 7 that I’d have to look up (“Michaelsmas term”, “Lord Chancellor”, “Lincoln’s Inn Hall”). As a consequence, upon reading the first sentence I immediately lose interest.6 Can I read this text if I have to? Yes. Do I want to? No.

Anyways, I’m sure American college students are as challenged at reading comprehension as the study claims, but nevertheless the study approach bothers me. When we make students read prose describing a world that is entirely alien to them, using numerous words and concepts they cannot relate to, is it so weird that they might not understand, and more importantly, might not be motivated to make a real effort?7 I’d very much prefer an assessment of reading comprehension where the material is more contemporary, so the question of whether students can comprehend the writing is separate from the question of whether they have intimate knowledge about living in 19th century England.

There’s one part of the study that truly irritates me. It recounts how a study participant describes a brief excerpt from Bleak House. A quote of the relevant part of the study follows below. (You can read the study in its entirety here.) In the quote, the excerpt is labeled “Original Text,” the study participant is labeled “Subject,” and the person interviewing the subject is labeled “Facilitator.” The paragraph at the end of the quote is the take-away of the study authors.

Original Text: On such an afternoon, if ever, the Lord High Chancellor ought to be sitting here—as here he is—with a foggy glory round his head, softly fenced in with crimson cloth and curtains, addressed by a large advocate with great whiskers, a little voice, and an interminable brief, and outwardly directing his contemplation to the lantern in the roof, where he can see nothing but fog.

Subject: Describing him in a room with an animal I think? Great whiskers?

Facilitator: [Laughs.]

Subject: A cat?

Note that the subject, who is not accessing any of the concrete details in the passage, finds a subject (the Lord Chancellor) and one recognizable word, [End Page 9] “whiskers,” and concludes that the character is in a room with a cat. At this point, she does not seem to understand what she is reading, and so she links a few words together to form some kind of response.

I find this interpretation of the subject’s response condescending. Assume you know nothing about Bleak House but otherwise have good reading comprehension. Now re-read the quoted text. Is it so weird to read “whiskers” and think about a cat? In particular, imagine you’re a contemporary student, who may have grown up with material such as The Wizard of Oz, Wicked, or Harry Potter, where animals take on major roles in the story development. Really put yourself into the position of the subject. You’re reading a weird book, about a weird world that doesn’t seem anything like your own, but that maybe reminds you of fantasy movies or similar material you have been exposed to. Now you read “addressed by a large advocate with great whiskers” and maybe you go “well, I don’t really understand this, but let’s assume in this world animals can talk and work as lawyers, and so maybe this advocate here is a cat.” I think this is a perfectly reasonable conclusion to draw.8

I’m sure most English majors consider reading something like Bleak House purely as a study assignment. Not something anyone does for fun. And how can you blame them? Just because it’s a classic doesn’t mean it’s enjoyable. Who decided that if you’re interested in the English language you also must like the culture and way of thinking of 19th century England?9

In my opinion, if we want students to read more, we need to introduce them to texts they can actually relate to and enjoy. I don’t know what those would be, that’s outside my area of expertise. But I personally have read plenty of books by different authors and there have been many that grabbed me, and yet I’ve never been able to make it even half-way through one of the 19th century classics. I’m just not interested in the worlds they describe. I can’t blame US high school or college students for feeling similarly.

Hemingway, I have to assume, was simply ahead of the curve when it comes to writing simplistic modern English for an audience that can no longer handle complex sentence structures.

To be fair to the author, the figure about the number of words per sentence shows the full distribution and variance is not increasing in this case. Though as a statistician I’d immediately want to know whether Simpson’s paradox may be at play. Are the types of books that are included in the analysis similar over time or are there major shifts we would want to investigate?

Carlson et al. (2024) They Don’t Read Very Well: A Study of the Reading Comprehension Skills of English Majors at Two Midwestern Universities. CEA Critic 86:1–17. doi:10.1353/cea.2024.a922346.

The study acknowledges this: ‘According to Wolfgang Iser in The Act of Reading, one’s ability to read complex literature is partly dependent on one’s knowledge of what he calls the “repertoire” of the text, “the form of references to earlier works, or to social and historical norms, or to the whole culture from which the text has emerged”. […] With Bleak House, this knowledge is crucial.’ (Carlson et al., 2024)

You can read the entire book here right now, on whatever screen you’re consuming this post. Such is the power of the modern internet.

I’ve never read the book, but I have watched the fifteen-part BBC television drama serial adaptation. It was dreary. And as you can see, I know fancy English words such as “dreary.” I should probably have remembered the Lord Chancellor but have to confess I didn’t.

Keep in mind that students may be doing poorly in the study either because they genuinely can’t read well or because they think the entire thing is ridiculous and can’t be bothered to make an effort. It’s difficult to tell these two causes apart.

I found an illuminating blog post about whiskers on humans. Apparently it was all the rage in 19th century England. However, I believe US English majors can be forgiven for not having read this post.

I genuinely would rather read a book on English grammar or copy editing than Bleak House. This is a good one: Claire Kehrwald Cook (1985) Line by Line: How to Edit Your Own Writing. So is this one: Lyn Dupre (1998) Bugs in Writing: A Guide to Debugging Your Prose.

That defense of the "whiskers" interpretation works for me! Good points and generous.

Isn't the point of 3-hour podcasts that you listen to them to reduce the tedium of sitting in traffic or doing the dishes or whatever? If it takes "serious focus and effort to sit through one," why would people do that rather than just reading a transcript?